David Lynch

The robin and his bug.

José Saramago wrote on his blog how despite personal vanities there are fundamentally two kinds of writers: those that create a new literature and those who imitate. Among the former are writers of the caliber of James Joyce, Gabriel García Márquez, Franz Kafka, Marcel Proust, Virginia Woolf, Clarice Lispector, and of course Saramago himself. Their originality derives primarily, as Mario Vargas Llosa tells us, from their fiction's relationship with reality. Tolstoy succeeded in writing novels that are colossal reveries experienced as real life. Proust's reality is on the level of memory, and how the remembrance of a single instant in our lives gives way to an almost infinite array of sensations, like a ray of white light going through a prism and splitting into a full range of colors.

The same goes for cinema. Lucrecia Martel, Carlos Reygadas, Robert Bresson, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Andrei Tarkovsky are all directors inimitable all for their own unique reasons, in equal parts expressions of their cultures (or cross-pollination of cultures) and an entirely singular human phenomenon.

David Lynch belongs in this category. All of cinema is dreams, yet Lynch succeeded in articulating a truly oneiric logic to his films. Suddenly by use of framing, lighting, montage, a simple staircase in a house becomes one of the most frightening objects I have ever seen on screen, granted a kind of subconscious aura, as though it were a veil hiding an unimaginable nightmare. These dreams seem to possess a mythology of their own. While his protagonists somehow feel a strangeness to their world, perceive their reality as uncanny–his killers move through the nightmares like predators in their natural environment.

The objects and characters that inhabit these dreams seem ancient. One feels the monster hiding in the parking lot in Mulholland Drive has been there forever, will be there forever. Same goes for the house in the middle of the desert in Lost Highway, a house that as Mariana Enriquez notes is both consumed by fire and itself consumes the fire.

And yet so masterfully his cinema sublimates from horror into a kind of golden beauty, elevated by music, exquisitely suspended there. These transitions from horror to beauty, to glamour, to eroticism, to then the most banal comedy, and then straight back into a still deeper nightmare are astonishing in their elegance, in the invisibility of their editing, the mastery of a sound design that is second to none. The spectrum of atmosphere within his films is dazzling. It makes a mockery of all so-called conventions, rules, and genres. Even his most noirish cinema is a portal to explore these dream realms, his detectives lanterns lowered into the darkest parts of human nature. Artists like Lynch make a mockery of genre because they are sincere enough to become genres of their own.

During a lecture titled From Poe to Valéry, T.S. Eliot said that Edgar Allan Poe's work should be judged as a whole, lest as the mere sum of its parts it seem inferior. The magnitude of Poe as a Romantic artist only reveals itself when reading his tales as well as his poetry and essays. The same I think is true for David Lynch. He has no single masterpiece, no one major synthesis of his work. The remarkable artist that he was only comes across when regarding his whole filmography, including his disturbing short films, his television series, paintings. Even his weather reports.

And like that house in Lost Highway, the art of the greats is both devoured by life and itself devours life. Their deaths are oddly foretold in their work. Tolstoy died in a very similar manner to one of his characters. Of fragile health from a lifetime of smoking cigarettes, David Lynch died in the midst of an apocalyptic fire consuming his beloved Los Angeles. The images of the conflagration seem born straight out of his cinema.

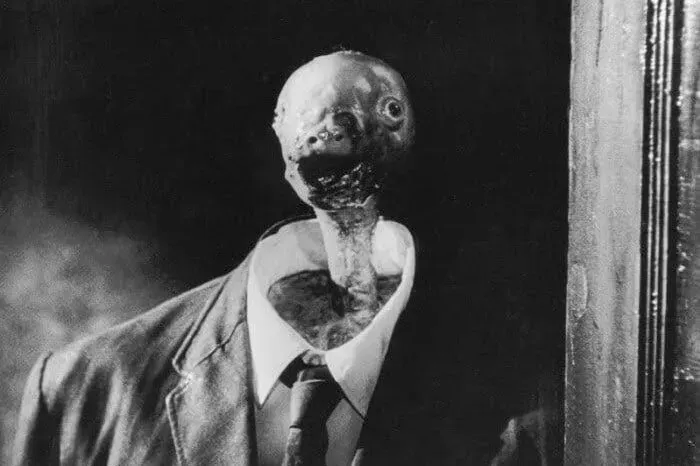

When I think of David Lynch, I immediately remember that trademark grin of his, a smile that articulates the joy of making art, of daily inhabiting art. I think it also best embodies the source of his originality. Because beyond the oneiric quality of his work, Lynch's films express the intertwined horror and beauty of our reality: the roses before the white picket fence, the severed ear (which later is so masterfully returned to the ear of Kyle Maclachlan woken from dreams by the robin's song), the couple having sex in the desert illuminated only by the car's headlights like some artificial sun in the nothingness, his horrid killers, the Mystery Man, the crying creature in Eraserhead–horror and beauty, American Dream/American Nightmare, the mundane and the uncanny are all intertwined in a perspective towards life that is so wise, so unique, and so happy. Having lived for a decade in Vancouver, I've come to understand just how much of what we call Lynchian is present and material in this reality. Lynchian places, Lynchian people, Lynchian creatures exist everywhere.

Like the robin eating the bug at the end of Blue Velvet, the artist carries in his beak a creature that is horrid, fascinating, and so curiously beautiful. It is the Lynchian smile that speaks with a mouthful of marvels the final line of the film: "It's a strange world, isn't it?"