Jean-Luc Godard

The objective of realism is to achieve the illusion that the art experienced is not the product of artifice, but that it miraculously generates itself as it is being consumed. Flaubert in his correspondence famously wrote a writer should be like God: present everywhere, visible nowhere. The greatest merit of Tolstoy, the finest realist writer who ever lived, is that as an artist he is invisible. We feel his characters are living people we are following in their day to day. We read Anna Karenina as a vivid dream, actively participating in the settings and situations that are crafted with such mastery, they feel as though they are our own experiences. Very few times we wake to the fact his novels are merely words. The same is true for a great deal of cinema. The thrill of many Hollywood films for instance is that during their runtime we believe their world, however simplistic or flamboyant, to be real.

In the early twentieth century, the German playwright and poet Bertolt Brecht advocated for the exact opposite. Brecht suggested an alienation or distancing effect in which the artist from the start would let the viewer know they were experiencing art and not reality. Tennessee Williams for instance opens his play The Glass Menagerie with the character addressing the audience, stating he is both a fictional person and the narrator of the play. “I am the opposite of a magician. He gives you illusion that has the appearance of truth. I give you truth in the pleasant disguise of illusion.” When music starts playing, he says, “The play is memory. Being a memory play, it is dimly lighted, it is sentimental, it is not realistic. In memory everything seems to happen to music. That explains the fiddle in the wings.”

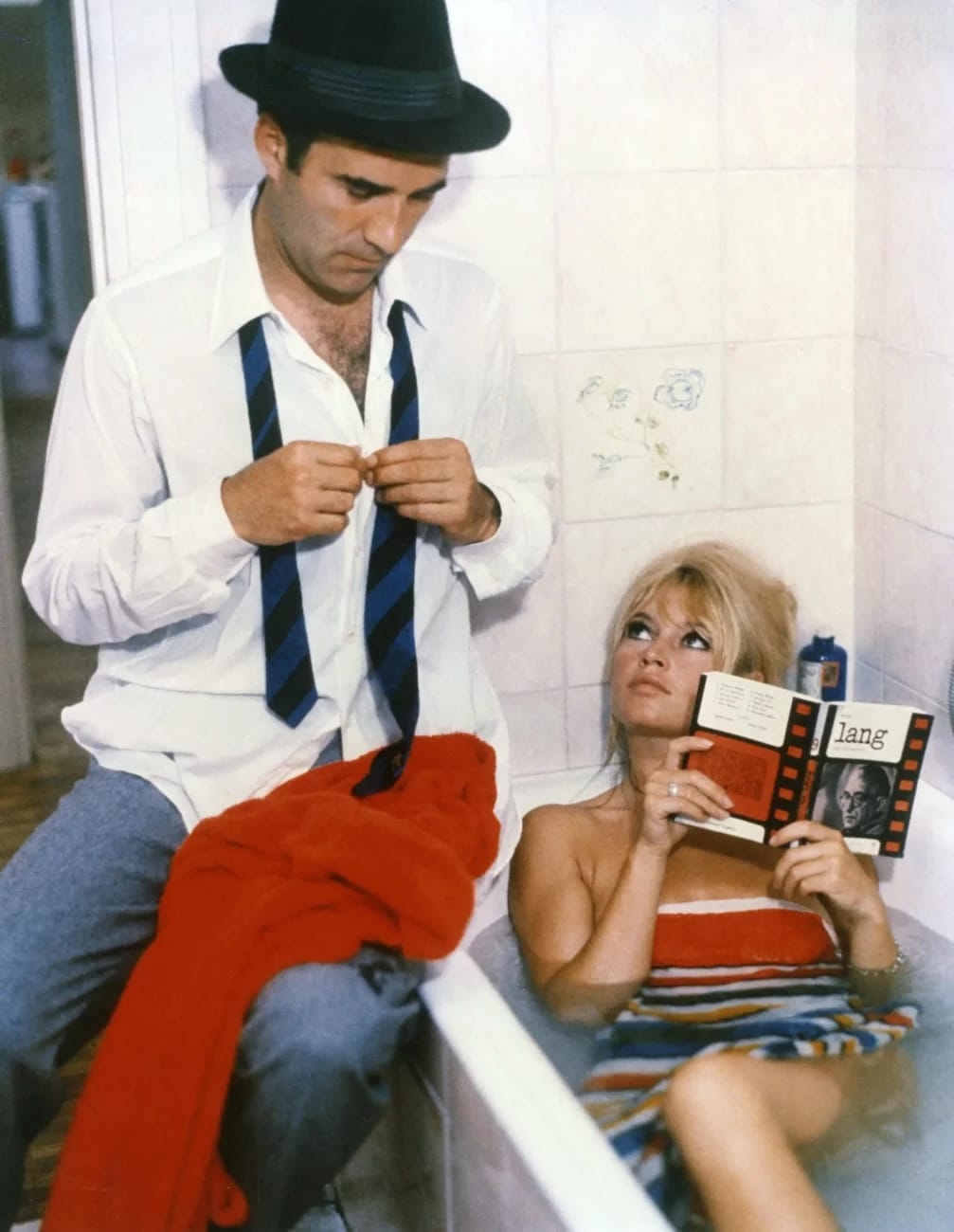

Jean-Luc Godard was not a director attempting to mimic reality. Instead he was interested in the nature of cinema itself, particularly cinema as a vehicle of ideas. In other words Godard was interesting in cinema as language. His characters are closer to metaphors than people. The protagonists are usually the same: the archetypal noir antihero, the classic hard-boiled detective with his trench coat, hat, and smoking cigarette. This is not so much a person in the world of the film, so much as the world of cinema itself, an archetype that Godard wields in different ways according to the context. In Le Mépris the screenwriter protagonist dresses and acts like this. As a typical Humphrey Bogart character, he engages in sleazy dealings when he agrees to write for money a Hollywood screenplay, an act of utter corruption for Godard. In Le Petit Soldat, the protagonist is again this noir figure, and I was unsure whether he was a photojournalist, an agent engaged in counter-terrorist activities, or simply the excuse of all these things.

Plot in these films is a frame for his ideas, an excuse to develop them. Instead of objective realism that strives to describe reality, Godard’s is a subjective and idealist cinema (the closest counterpart in literature I can think of is Joyce’s Ulysses, where literary archetypes and mythical figures are employed in a similar manner). More often than not his ideas are usually relating to art. The very tissue of his cinema is not life but art. Le Petit Soldat is a film supposedly about spies during the Algerian War, but suddenly the protagonist starts telling us why he prefers to listen to Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto in the mornings as opposed to Mozart at midnight, before breaking into dance listening to Haydn. He describes Anna Karina as having “[Diego] Velázquez eyes.” Even the Algerian War is more keenly explored through lengthy dialogue about nationalism and what he feels it is to be French (which is to love the idea of France more than the physical territory), than with the actions of the supposed spies themselves.

The greatest and most harrowing moment of Le Petit Soldat is the torture scene, when the film goes far beyond realism and shows us actual violence. In this context, violence is like a specimen delivered for our questioning and observation, and I was deeply disturbed by how indifferent I felt when I first watched it. In Le Mépris Godard does something similar but with the idea of beauty, when Brigitte Bardot is naked on velvet sheets, reciting curse words.

Godard’s films are like a conversation taking place during a long walk: they are filled with digressions, interruptions, ellipsis. They are punctuated by occasional moments of insight and brilliance, always combined with pause, silence, and contemplation. Unlike in realist cinema, Godard makes himself present in his movies because his ruminating perspective is the driving force of his films. He is very much like Montaigne both in the strength of his perspective and in the sense his films constitute essays or “assays,” trials and attempts at clarifying truths. His films are living texts to the degree that I often feel like I’m reading a book when I watch his cinema. Many times he’ll even deliver poetry: “Most people talk on and on like gold prospectors to find the truth. But instead of dredging in a river, they dredge among their own thoughts. They eliminate all the words of no value and end up finding just one. But a single word by itself is already silence.”

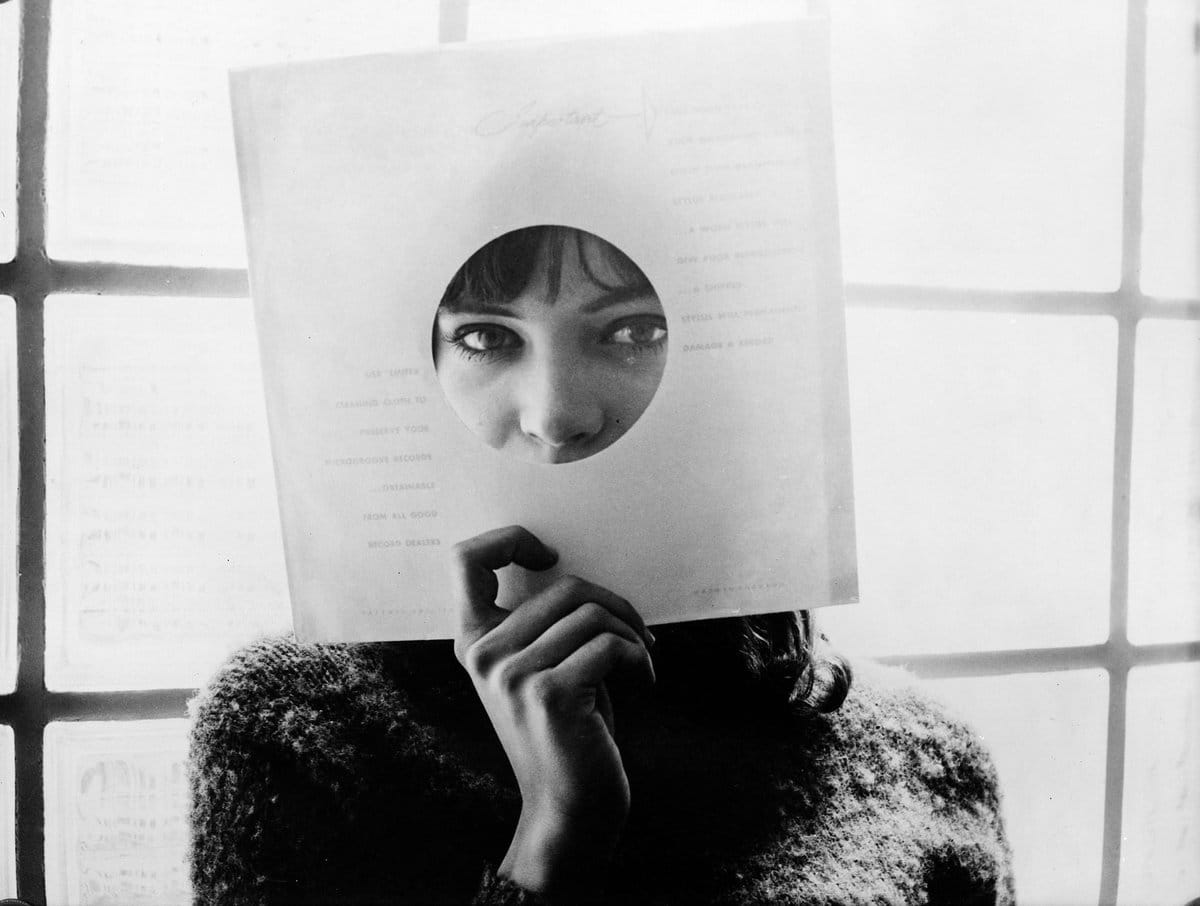

For Godard cinema is not an exclusively visual medium. Listening plays as much a part in his films as contemplation. There are images within the film that appear to us though we never see them, for instance when the protagonist of Le Petit Soldat taunts us by never knowing what he’s thinking: “A forest in Germany, a bicycle ride. That’s gone. Now… the terrace of a café in Barcelona. Now… that’s gone.” Thought is language, and language consists of images as well as words. A cinema that is relentlessly thinking, examining, brooding can only be both.

Vivre Sa Vie is the best film of his I’ve seen. Le Mépris is his most direct. In it a Hollywood philistine commissions Fritz Lang to shoot an adaptation of The Odyssey. I think the last shot of the film is particularly emblematic of Godard’s approach. Le Mépris ends with the crew shooting the scene in the movie when Odysseus first glimpses Ithaca, his native island from the distance. But when the camera pans to show us what he’s looking at, there is only ocean without end. Home is nowhere in sight.

It is quite a painful moment that sums up the commodified state of art in a capitalist world, but I also feel this idea of a search exemplifies Godard. “Photography is truth, and cinema is truth twenty-four frames per second.” Godard’s camera is not interested in capturing life, or even in the relationship between life and cinema—but in extracting truth from life. His cinema is a dialectic. It constitutes a process and a journey.

I want to clarify that when I say his cinema is language and ideas I don’t imply it to be dispassionate. Quite the contrary, like the finest modernists Godard’s greatest virtue is his bravery. He dared to be an innovator of the form. He often failed, and he was comfortable with this. As he put it, “He who jumps into the void owes no explanation to those who stand and watch.”